Steve Jobs wanted the personal computer to be like a “bicycle for the mind.”

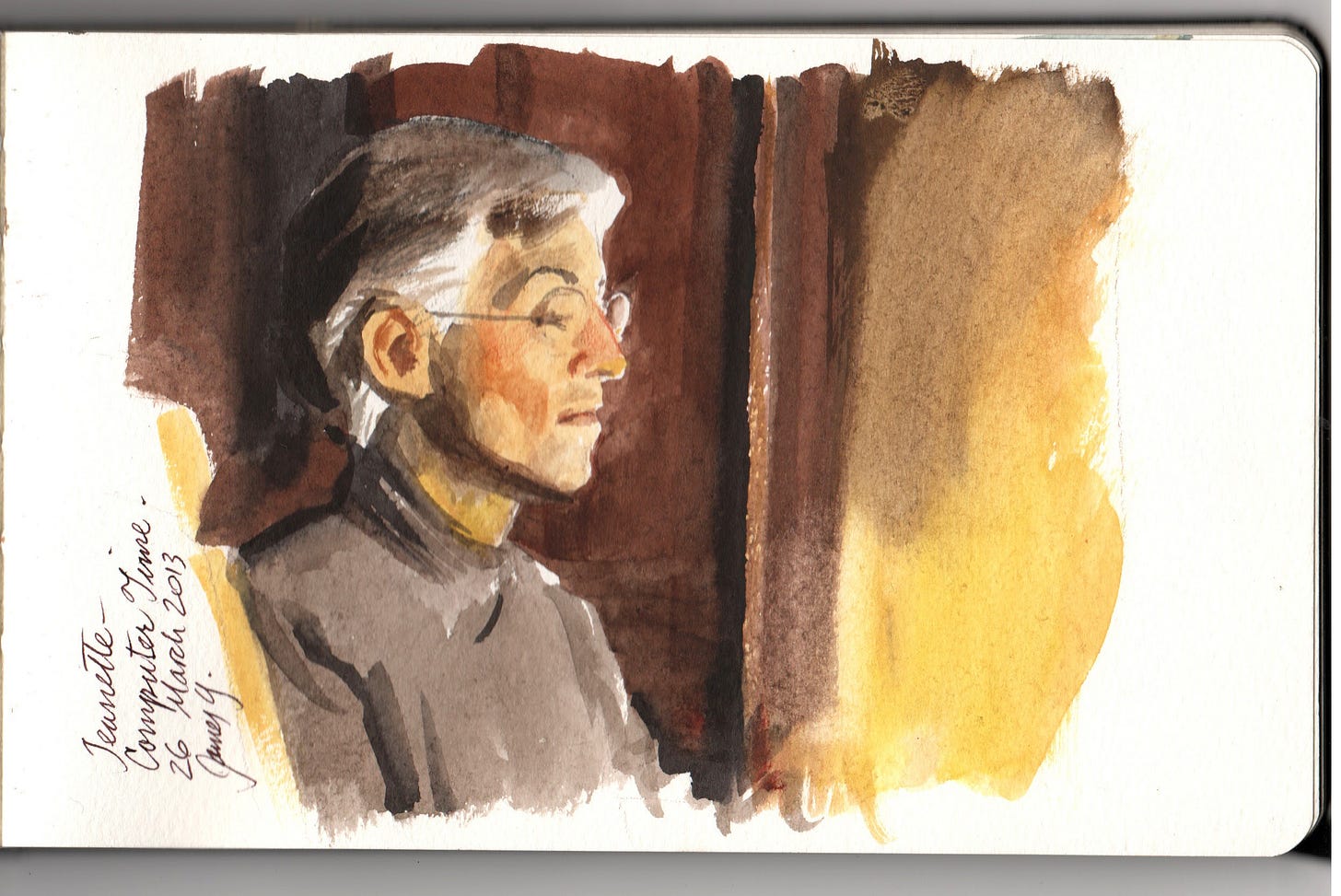

(Sketch of my son Dan doing homework on our computer workstation in 2000.)

It felt like that at first. It carried us to amazing places, introduced us to new people, showed us to new things. In many ways it amplified our capacitie and empowered us.

(Photoshop Battle) from life, 15 minutes

Then the computer became more portable. Laptops, tablets, and smartphones made it a constant companion. Screens began to surround us, no longer confined to a single room.

(Sketch and list of car models)

Over time, using a computer became more like driving a car. Each year, the engine grew more powerful, the traffic thickened, and the speed limits increased. We raced through information highways filled with signs, rules, and flashing distractions. Algorithms steered our attention, while advertising pounded on the windows. We rolled up the windows and locked the doors, hoping for silence.

(Strutter from Dinotopia)

But the computer-as-car metaphor was still evolving. Now, our car has grown arms, legs, eyes, and a brain. AI meets us at every intersection, gently offering to take the wheel. It assures us it won’t harm us. We hand it the keys, let it take the driver’s seat, recline ours, and drift off to sleep

We wake from our nap. We’re still rolling along. But the automobile has become a motorized wheelchair. We can’t even walk anymore, we can’t think, can’t speak, can’t remember, can’t imagine. What happened to the clouds, the moon? Where's the town? Where is everybody? The grass has all become Astroturf. All we have is a fake replacement of the world we once knew.

Some of us are trying to remember or reconstruct the simpler joys of riding a bicycle, or even just walking, one foot in front of the other. We are reclaiming the ecstasy of movement, of unassisted thought, of unmediated seeing.

It sounds like I’m arguing for living in a log cabin and going off the grid. But I’m not preaching or advocating for any set of choices. Each of us has to make our own peace with the machine, and the choices we make will vary from person to person.

We don’t need to live in one mode all the time. Just as we can switch from walking to bicycling, hiking, or taking a train to the next town—what once would have taken a week on horseback—our cognitive lives can shift between modes.

We can sketch observations in a notebook, then let AI help us refine a pitch or sharpen a sentence.

What matters is that many new technologies aren’t just offering shortcuts—they’re designed to replace our cognitive muscles: memory, imagination, songwriting, even decision-making. Is that a good thing? Will it make us stronger? Will it make for better art?

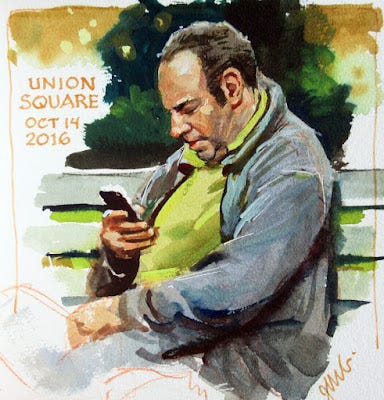

(Sketch from life in New York City)

It might do so in the short term for some of us who are both adept and motivated. If they or we use these resources in the right way, without letting our native abilities atrophy, we’re potentially capable of incredible achievements. Maybe one person can make a great feature length movie.

In the muscular world, it’s worth noting that Olympic records keep getting broken. If that dynamic applies here, we may be entering an era of “supergeniuses”.

But most people aren’t Olympians. Most of us aren’t that disciplined. For people who are OK with letting machines do the hard work, we may be rushing into a profound and possibly regrettable experiment.

I can’t help asking a really fundamental question that ethicist Michael Sandel posed about AI on a recent podcast: “To what problem is AI the solution?”

The answer may depend on whether we choose to keep pedaling.

In the comments, I’d love to hear how you’ve made your peace with digital technology. Have you been using it differently recently? What aspects of your computer life frustrate you or alarm you?

I am wrangling in the last few weeks with the unwelcome disruption of AI into everything, from Microsoft 365, Google all the way to Amazon Music. I don’t want a CoPilot, an AI synthesis of search answers, or a song that Amazon thinks I’d like. I am much happier making my own way.

"Every augmentation is also an amputation." --- Marshall McLuhan