Why Can't They Make a Movie Out of Dinotopia?

People have tried, but there are definitely some major challenges.

Why can’t there be a great movie or series made from the Dinotopia franchise? It seems like a natural idea: here’s a New York Times bestselling illustrated book with an extravagant premise, a deep prehistory, and plenty of dinosaurs.

It’s not easy to create an adaptation of the first two books that preserves the utopian appeal of the world, but also introduces enough conflict to make it work as a three-act drama for adults. If you make it too sweet, it feels corny or preachy; but if you give it too much edge, it feels wrong for Dinotopia.

Of course, Dinotopia has already been a TV miniseries and a short-lived series back in 2002. The production was pretty ambitious for its day, and it won an Emmy. But it didn’t have much resemblance to the books, as it was set in another century with all different characters. I saw it only once, at a neighbor’s house, because we didn’t own a TV or any way to play videocassettes. I felt a mixture of emotions: grateful and honored that my books were given such a lavish treatment, but totally detached, as if I was trying to enter someone else’s imaginary world.

What are the challenges in adapting Dinotopia to the screen?

I’ll be the first to admit that Dinotopia presents some formidable challenges to movie or TV adaptation. It lacks a three-act structure. It’s episodic and sprawling, without any strong conflict or peril for the main characters. The illustrated books are not focused on the characters, but on what they see. The utopian aspects of the world, which are so appealing in the books, quickly become dystopian if the story tries to address law, crime, economics, politics, diet or religion. There’s no bad guy or threat. If, in an effort to give the story more drama, you set up a group of malefactors to threaten the utopia, the whole concept becomes repellant and the audience starts rooting for the bad guys.

I recognize that the book’s story needs to change to work on the screen, but there’s no obvious way to do it. Since 1993, some of the most famous screenwriters, directors, and producers have valiantly tried to adapt the books, but most have given it up. These difficulties are somewhat intentional. I perversely wrote and illustrated a book with the thought that it could never be made into a movie.

The audio adaptation of the first two illustrated books by ZBS Productions was a glorious exception to this rule. The books worked well as an audio dramatization, because it followed the books very closely in both letter and spirit. The audio drama was made by a small group of people on a tiny budget, and anything is possible in audio. But putting the whole book on screen would never work. It would be far too costly and dramatically unfocused.

How I came up with the original idea

To explain the challenge of adapting the books to film, it might help to take you back to my own struggles when I was coming up with the original Dinotopia book. There were many false starts, each one based on a wrong assumption, forcing me to make ruthless revisions.

Before I came up with Dinotopia, I first thought in terms of a faux travel guide of lost civilizations, illustrated with pictures of Atlantis, El Dorado, and Seven Cities of Gold. It seemed like a good idea at first, but it had been done before, and the reality of each domain cancels out the others, because they can’t all exist at once. So I discarded that idea and all the work I did on it.

Then I decided to make the book about a forgotten world of dinosaurs and humans, with the inciting incident being the discovery of underwater ruins by a submersible. I would chronicle the news media coverage of this discovery and then take people back in time to the heyday of the world. But that framing device wasn’t appealing. Having the world drowned on the ocean floor eliminated the opportunity for utopian wish fulfillment. So into the wastebasket it went.

After that I came up with the idea of a contemporary scientist who finds an island and returns to describe it to the outside world. No one believes him. He’s got these pictures to prove it. But I couldn’t get past the obvious fact that a big island could never escape the gaze of modern satellites, making the suspension of disbelief impossible. Another trip to the dumpster with a lot of writing and artwork.

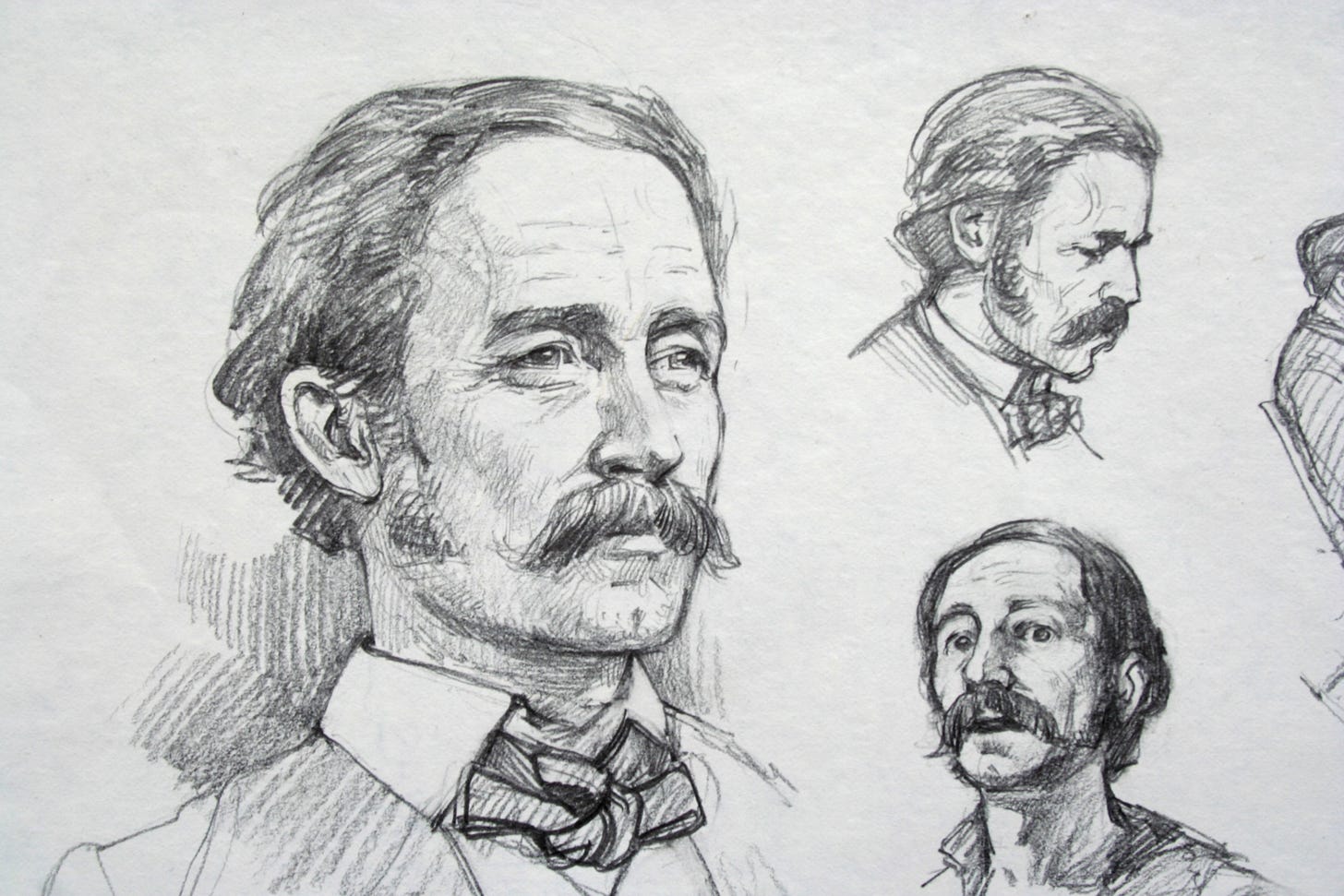

Then I resolved to set the story in the mid-19th century, when there were still blank spaces on the map. I made my point-of-view character, Arthur Denison, a kind of Renaissance man who has just been exposed to Darwin, but he isn’t a believer in evolution yet.

This idea was more promising because the journal conceit provided a voice, a look, and a format. The 19th century was a time when our western world was making a lot of fateful decisions that have shaped our current experience: electricity, motor transport, manufacturing, etc. Having a story told by someone who was a champion of progress would allow me to present a credible utopia that carried some clout for our times. This had potential.

In early storyboards and outlines I had developed a long sequence in Hong Kong introducing the characters and building the mystery. We follow Arthur and Will as they provision the ship, and we flash back to Arthur’s past life in America and hint at why he left for this expedition. I ended up cutting all that out and starting the story as late as possible, with the shipwreck. I dispensed with all framing devices and took the reality of the world for granted.

By this time I had about 25 pages of the story mocked up. I had a detailed outline, and a complete storyboard. Several leading publishers were interested. But some of them expressed a hope for a more dramatic story, with the paradise world threatened with destruction, a world in peril. To explore that idea I developed a secret underground army led by Lee Crabb, who would harvest enough guano to blow up Waterfall City and send it into the chasm. I showed the new storyboard to Betty Ballantine, my editor at the time, and she said: “You can’t make it better by making it worse.”

That line stuck in my brain for a few weeks. She was right. I abandoned what I had outlined about Lee Crabb’s army. I realized that the whole appeal of this idea was to go against the Hollywood mainstream idea of an epic conflict between good guys and bad guys. I tried to flesh out a world that was truly harmonious, where humans and dinosaurs lived in peaceful interdependence. That wasn’t easy, because utopias can be boring or preachy. I carried on because I knew that sensibility would work for art prints and illustrated books, but I wondered if it would ever be adaptable to movies, TV and games?

The book was a New York Times bestseller in 1992. The next year we optioned it to Columbia/Sony pictures.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Paint Here to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.