What Should They Teach at Art School?

Readers share their thoughts about the art education curriculum

Should art schools focus on the fundamental skills of drawing and painting from observation?

Some people don’t think so:

"Drawing from observation and nature and commonly from the life model has been actively discouraged,' says Andy Pankhurst, an artist who teaches at various institutions including the Royal Drawing School. While teaching at Slade during the early 00s, students told him they were no longer coming to his life drawing class because other tutors had told them if they did, they would turn into vegetables. 'They were being told that working from observation meant you had no concept or ideas.'"

(Quote from the Guardian: Should all art students learn to paint and draw?)

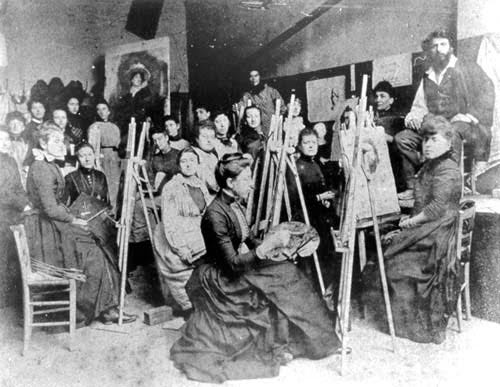

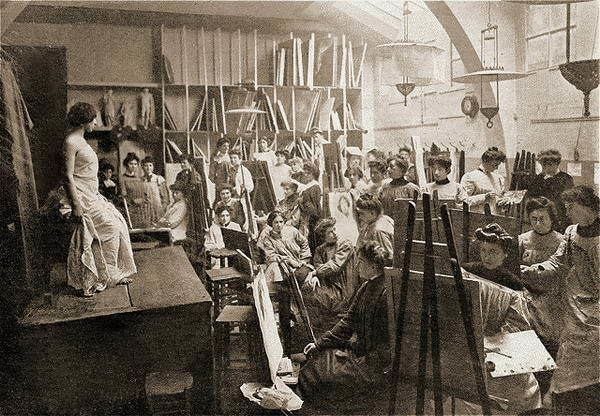

Most people are familiar with the basic teaching approach of the modern Bargue-based atelier movement, which focuses on observational skills of drawing and painting, mostly from plaster casts and nude models.

No one debates the necessity of classical skills at a music conservatory.

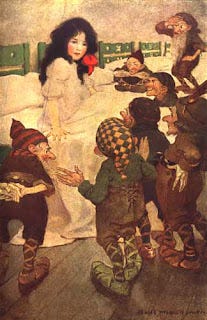

American illustrator Howard Pyle, in his summer classes, didn’t teach that at all—though his students typically entered his program with that training already in place.

Pyle didn’t talk about technique or observational methods. Instead he made the story paramount. Pyle’s student Jessie Willcox Smith recalled how one’s awareness of the story influenced the choices in composition:

"At the [Pennsylvania] Academy [of the Fine Arts] we had to think about compositions as an abstract thing, whether we needed a spot here or a break over there to balance, and there was nothing to get hold of. With Mr. Pyle it was absolutely changed. There was your story, and you knew your characters, and you imagined what they were doing, and in consequence you were bound to get the right composition because you lived these things. . . . It was simply that he was always mentally projected into his subject.”

And then there’s the big question facing art schools now: How should these institutions respond to the new era of generative AI? Should they exclude it or embrace it? If they want to ban it, how can they? And if they want to embrace it, how do they find teachers and how do they keep current with workflows that change daily?

So to summarize three curriculum strategies referred to so far:

Teach practical skills of observational realism.

Focus on storytelling and composition and downplay technique.

Stay current with what professionals are actually using in the marketplace.

Obviously a given school can offer multiple approaches at once, but no single student can learn everything and master it all.

THOUGHTS FROM E.A. ABBEY

A century and a quarter ago, the great illustrator/painter Edwin Austin Abbey (above) laid out what he saw was wrong with American art education and how to fix it:

“It seems to me that no one could seriously dispute the fact that a great school of art in America is needed, or that such a school would have the very greatest influence in the development both of the spirit and the practice of art. As art is now taught in this country, it is too fragmentary. The pupils are not thoroughly grounded. Any one who wants to study art here can do so. The examinations are too easy. In the foreign schools the examinations are very difficult. The student must know a good deal to pass them. There should be an American school with equally high requirements.

If a young man [or young woman] wants to enter Harvard or Yale, his preparation must be thorough. That is the way it should be with the school of art, for the school of art should really be like a university. The student, before being admitted to the university, should have passed beyond the elemental stage of study which properly belongs to the grammar-school grade. As it is now in America there is no place where parents who think their son is a genius can send that son to find out that he isn’t a genius. There are very few people who can’t be taught to draw more or less well, but the mere ability to draw does not make an artist.

"There seems to be a desire on the part of a very large number of persons either to become professional artists, sculptors, and painters or to acquire some of the principles of decoration. But there is also widespread ignorance that a thorough grounding in certain facts is absolutely essential to the serious student before he is prepared to avail himself of the experience of others.

Those who wish to study art here are admitted to classes far too leniently. In the schools abroad the entrance examinations are very severe, and by a succession of examinations, the less talented are eliminated. This refers, of course, to the great schools — not to the irresponsible studios, where a model or two is hired and a few painters with a present reputation are engaged to call in occasionally to give advice; to such schools anybody, with no experience whatever, can, by paying a small fee, be admitted.

It has been immensely to the advantage of America that there is nothing for architects abroad which corresponds with the irresponsible painting ateliers referred to. The student of architecture going to Paris, for instance — although my remarks do not apply to Paris alone — can only study his profession by going into the “Beaux Arts.” The entrance examination is very severe, of course, and should be so, but the effect upon the American student is everywhere apparent here, and has given the architects of the United States the great position they occupy to-day.

If the money is provided — and one of the things which surprises me on coming back to America is the amount of money there seems to be — there would seem to be no reason why a great American school of art should not be established and be put in working order within a reasonably short time. A building should be furnished, among other things, with copies of the best examples of art in foreign countries in sculpture, painting, and architecture. There would be little difficulty in acquiring these, although it would take time.

The American Art Federation would be the institution which would most naturally father the work of establishing an American school. And the question of a location for the school would have to be answered by circumstances. It should be in a center, some place where it would be to the advantage of both pupils and instructors to live. The location might be a problem. One would name New York as the obvious place for the school, as the National Academy is there, and the various art societies to which most American artists contribute hold their exhibitions there.

The art ability of Americans is not to be belittled. The best American artists can hold their own anywhere. American art as a whole, however, has the tendency to be preoccupied with problems of a technical nature, such as how to put on paint, and things of that sort. The painting of individual pictures is not art in its highest form. Pictures are only fragments. The great things are works which carry an idea through to completion.

I do not think that the great problems of adapting one subject or composition to its environment is sufficiently studied, if it is studied at all. The three great branches of art — painting, sculpture, and architecture — should be independent. Without a knowledge of the other two, each is incomplete. The restraining influence the study of each one has upon the others is of the greatest importance and of the greatest service.

A school should have, first of all, the great artists of the country as overseers. That is the method pursued in Munich, where the great artists are given studios in the school, and the students are allowed, several days in the week, to consult them about ideas. In addition to the influence of American artists of first rank, the American school might also make arrangements to receive the benefit and advice of prominent foreign artists who are visiting this country from time to time. As to the instructors, there should be many of them, and there is no reason why they should not be drawn from the ranks of American artists.

The curriculum of the school should embrace sculpture, painting, and architecture, and every student should be made to learn something about all three branches of art. There are many Americans who are quite competent to act as instructors, under the supervision of artists of first rank. And the great thing is that the school should have one inspiring head. The advantage of having great artists on the staff, to whom students can have access, lies in the fact that one can learn much more by working with a man than by simply being told what to do, or what not to do. The establishment of the school would mean, primarily, the sifting out of the incapable. It would push forward those who had real talent, and would discourage those without talent.

An art atmosphere is hardly to be spoken of as something which is created; it is rather something which happens. It is a matter of tradition. A whole country grows up to art, and the atmosphere comes gradually into being, one can hardly explain when or how. And a people who have once developed an art atmosphere may degenerate. Take Italy, for example. The Italy of the past was a paradise of art. Rome is an eternal city because of the handiwork which immortal artists have left there, if for no other reason. But take the Italy of to-day—where is its art atmosphere? The average modern Italian likes the worst pictures and loves noise. It would seem as if all the art air had been breathed over there. An art atmosphere is not generated entirely by pictures. The kind of houses men build, and what they put into them; the decorations of public buildings; the beautifying of public parks; the care of the streets, all these things play important parts. In this day, it is not so much the love of pictures as care for vital things which needs to be encouraged.

The generating of an art atmosphere requires a great deal of money, as well as a great deal of good taste on the part of a great many people. Public building decorations of the highest order are so expensive as frequently to make them impossible. The artist who does the work, too, must inevitably make sacrifices. But the man who takes up the profession of art must have higher aims than financial considerations. The painting of an important and thoroughly careful work is much more expensive than most people realize.”

INITIAL COMMENTS FROM READERS

Pieter Verhoeven Installation artists only need basic drawing skills, same for 3d modellers, graphics design, motion graphics, photographers, data visualizers, typographers, collage artists, photo manipulators... etc etc.

Should we make typography, animation, topology, lighting, set design etc all mandatory?

The main aim of art school is to become a creative thinker, learn how to manage your timeframes, learning to know your strengths and weaknesses as a creative. In short, an intimate exploration of the creative process, with all the pitfalls that surround it. You can be an excellent draughtsman or photorealistic painter that completely fails at interpreting briefs or have no philosophical or conceptual foundation and just end up producing surface level flash.

Teaching drawing to students opens some doors, but shuts others. By teaching a certain technique and set of values you are bounding his or her possibility space and setting them up on a path they might otherwise not have taken. You are teaching him or her to see the world through your eyes, reducing possible original discoveries. It might presuppose an idea of art as imitation. Making a value judgement on a piece of art requires a set of parameters used as a measuring stick as the basis of critique, but such parameters are not fixed or set in stone. Furthermore, observation is perception, which makes art deeply individual. Van Gogh is deeply anti-academic and never sold a piece in his life, yet now he is considered one of the greatest painters who ever lived.

Art school is not drawing school, there are plenty of drawing courses just like there are ones on music or film.

Bryn Barnard It is a very interesting question, as it goes to the heart of what the fundamentals of art actually are. If art is hand-eye coordination and the ability to replicate and interpret what we see though drawing and painting, then , indeed something crucial has been lost if we don't teach it and will be very difficult to regain. On the other hand, if art is more than skills, more a way of seeing and thinking, then perhaps those skills are not as crucial as we think. In the West, where our system of aesthetics goes back to the argument between Plato (who banned artists from his Republic because they were imitators of our reality, inflamed emotion, and hindered reason) and Aristotle (who appreciated art's cathartic ability), we have focused on the ability to render as synonymous with art itself. But that's not true of all, or even most art traditions. In the international schools where I teach, I have had students with brilliant drafting skills learned at art cram academies unable to do much beyond rote replication in the style of their masters and conceptually brilliant students without much drawing ability able to create art that brings audiences to tears. One does not negate the other.

Richard So I have been teaching for over 10 years. I have taught everything from Graphic Design, Illustration 3d and Game design. Every school that I have taught at has or has had the the fundamentals, everything from basic drawing, with perspective and anatomy, basic color, and design. The issue is twofold:

1. Students don't think about the basics when they start out, and really focus on the new project at hand. It doesn't matter if it's an illustration or a 3d model, they are more focused with the project than the basics of color, design and principle.

2. I think schools don't stress how important the basics are. One or two classes for drawing, a class for design and a class for color, if it's not shoved together with the design class. In my classes I often fail students for not getting/understanding the basics. And they fail to do so because they are so focused on the next step or process.

Michael Pianta. I think the issue isn't whether ALL students should learn these skills (as the question is put in the Guardian headline) but whether serious art schools should be able to offer this instruction to those students who are interested.

I went to a university, got a BFA, then subsequently attended an atelier and now teach at that same atelier. I have had many conversations with people about universities primarily ignoring, and evening denigrating "fundamental" skills. When I tell people about this, they often don't quite believe me. One time a woman who had a music degree was visiting the school - she was working for a city arts council that had awarded us a grant - and myself and the other instructors and the director were explaining that most BFA programs simply do not teach these skills. She could hardly believe it. It took all of us to convince her. I have had many similar conversations with donors, interested members of the public who have come to our exhibitions, parents and spouses of students and potential students, etc.

The comparison to music conservatories is apt, because everybody seems to assume that art programs work the same way - that is, students are free to pursue their interests, whether that's traditional classical music and performance or more contemporary, avant-garde styles. But at my BFA program (which was a very small program) the hostility to traditional realism was pretty entrenched. I know for a fact that a handful of students dropped out or changed majors because the faculty was so opposed to them pursuing traditional techniques and subjects. Another whole batch of us abandoned our early "realist" goals, and started making "contemporary" works, with various degrees of success. Exactly as described in the quote, we were all told that making realist work was unsophisticated, and that even knowing how traditional paintings were "supposed" to be made would ruin our creativity forever. Basically, you won't have to "de-skill" if you never acquire any skill in the first place. That seemed to be the dominant attitude in my department, and I don't think it was at all unique in that respect.

Jonathan Noble. Well, the problem is, as much as it is impossible to avoid the fundamentals of any sphere of activity in order to achieve facility.. there might be some truth in what these “tutors” were suggesting.

It’s interesting to note that the last line is “This question doesn’t come up at music conservatories” I mean it even says it in the name. The school is called a “conservation of music” not a “new conception of music. It’s not called a music conceptionary. And almost none of the great musicians that have changed and pushed contemporary western music in the last 100 years have come from a consevatory. Tons of incredible technicians. But the ones coming up with the new ideas, and pushing things forward and expanding genres: Almost universally avoid fundamental training except at the bare minimum needed.

Would Jimi Hendrix have even been Jimi Hendrix if he had all that music conservatory training? Well we could argue it, but any list of the 100 greatest innovators and creators in modern music history is going to consist of the primarily unschooled and mostly lacking fundamentals (beyond basic facility).

Modern western art is of course, not quite such a clear path, but when you really get down to it, the artists leading us to new genres and new approaches. The ones shaking the fundamental roots of popular culture. Well they mostly haven’t been completed by the type of personality that has the tenacity and diligence to work in an atelier countless hours year after year spending 30 hours making perfect charcoal drawings of plaster casts.

Or maybe, every time we practice fundamentals we are in fact grooving in those neural pathways, both in our actual physical strokes, brush movement, but also in the way we observe, what we observe and how we think about it.

Probably outright creativity would be hindered by too much pre drilling in of the neural pathways early in someones career. Probably we do have to, in some degree choose between utter creativity and utter craftsmanship, and probably even more so we are already prebuilt individually to be leaning more in once direction, and the other direction would likely be so onerous to us that the decision makes itself.

So I think probably the answer is, do what moves you. Because frankly if you don’t enjoy life drawing why are you doing it anyway? That’s the fundamental of all fundamentals for us to learn maybe.

Jamie Williams Grossman. Don't even get me started! This would never happen in the music education field because you'd never get audiences to listen to or buy the resulting music. In art however, we have curators who create spin around kindergarten-style works hung upside down, using verbiage to sell it to curiosity-seekers. Visual art should be able to tell its own story without a five page explanation. Personally, I think they feel threatened by artists who know the basics, and how to deliver a message visually, without a five page explanation. I recently went to DIA in Beacon and thought it would make a better roller skating/skateboard park! What a waste of space.

I know countless artists who say they never learned to draw in art school. You never find graduates of music schools who didn't study music theory, form and analysis, counterpoint, basic knowledge of their instrument, and usually a second instrument (piano for non-pianists). You don't find foreign language majors who didn't study grammar, or math majors who didn't take basic algebra. Imagine if software engineer majors just played video games all day, instead of learning code. This is not going to change in the art school world until conservators and galleries stop spinning art that doesn't meet basic quality standards.

A comment back to those who have spoken about differences in music and art:

Just as we don't know all the artists' names who have played a role in Pixar movies, or designed brilliant marketing design ideas, or do storyboard designing, or create characters, we don't see all those musicians behind the scenes who are making the musical world go round. It's not just pop music out there. It's true that if you just want to play a few chords and write rap lyrics, or throw paint at a canvas in pretty colors, you don't need to go to music school OR art school for that! (I am not denigrating popular music, which I do like. I'm just making a point about it. And if you want a great back up musician for your concert, you'll probably end up hiring one of those music school graduates.) As a music conservatory graduate, I can tell you that we all learned jazz, composition, arranging, and other creative forms of music-making. I see a clear parallel with art, where from the basics, one can go in many different directions. Without them, you're stuck inside your own world. If that's what you want, no problem; however, you don't need to go to school to be stuck in your own world.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Paint Here to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.