In architecture and design schools, it's common to hear the claim that "golden mean" geometry was used in the design of ancient buildings, especially the Parthenon.

According to mathematician Keith Devlin of the Mathematical Association of America, this is a groundless myth, with no basis in fact whatsoever.

The golden mean (also known as the golden ratio or the divine proportion) refers to the relationship of 1:1.618..., an irrational number also known as "Phi." The ratio is found in nature, and has been championed in the last two centuries, but many other claims are unfounded.

Although Greek mathematicians knew about Phi, there is not a shred of evidence that any Greek architect used such a system as a design principle. Euclid's study of Phi occurred long after the Parthenon was already finished.

Devlin says:

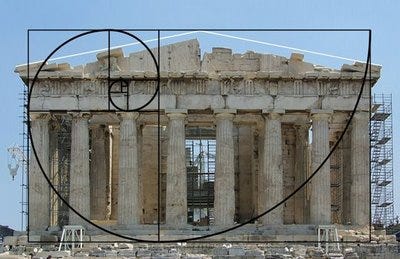

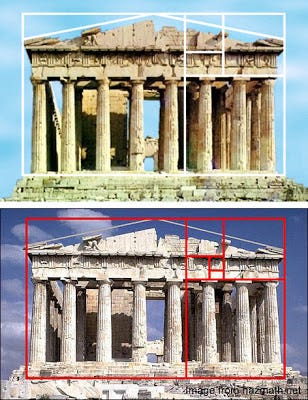

"The oft repeated assertion that the Parthenon in Athens is based on the golden ratio is not supported by actual measurements. In fact, the entire story about the Greeks and golden ratio seems to be without foundation. Numerous tests have failed to show up any one rectangle that most observers prefer, and preferences are easily influenced by other factors. As to the Parthenon, all it takes is more than a cursory glance at all the photos on the Web that purport to show the golden ratio in the structure, to see that they do nothing of the kind. (Look carefully at where and how the superimposed rectangle - usually red or yellow - is drawn and ask yourself: why put it exactly there and why make the lines so thick?)"

In the examples above, the placement of the golden rectangle doesn't agree from one diagram to the next. In the top example, the sides of the rectangle hug the columns, and in the next, they're touching the edges of the pediment. In some, the bottom of some rectangles correspond to the bottom of the columns, while in others, they're several steps down the base. In the middle example above with the white lines, the source photo itself seems to be stretched vertically by about 15%.

According to University of Chicago math professor Phil Keenan, it doesn't matter how you arrange the diagram, because the lines in the Parthenon aren't straight or parallel anyway due to entasis and other factors. He says:

"One cannot define an exact rectangle on the front or back faces of the Parthenon. Even though the Parthenon is built to extremely accurate specifications, its curvature precludes rectangular measurements of any greater precision than about 1%. This built-in error precludes finding any Golden Mean rectangles, since the required accuracy is simply not attainable."

George Markowky elaborates:"The dimensions of the Parthenon vary from source to source probably because different authors are measuring between different points. With so many numbers available a golden ratio enthusiast could choose whatever numbers gave the best result."

Keenan points out that, "the presence of the Golden Mean in the Parthenon was postulated by Adolf Zeising in the 1850s, and appears nowhere in ancient Greek architectural treatises."

Devlin concludes: "I am not convinced that the Parthenon has anything to do with the Golden Ratio."

Did Leonardo use the golden mean?

Let's consider whether Leonardo Da Vinci used this mathematical principle in his artwork. The claim that he did so appears in everything from modern how-to books on composition, to art school lectures, to popular novels such as Dan Brown's The Da Vinci Code.

Leonardo did several drawings of the idealized human figure set inside a geometric grid, including the so-called Vitruvian man, but it doesn’t show what people profess it to show.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Paint Here to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.