Discover more from Paint Here

Jean-Léon Gérôme’s wooden palette, 11 x 16 in., Baltimore Museum of Art, George A. Lucas Collection

Palettes appear in many paintings, especially self-portraits, and they reveal something about the artist’s thinking and working process.

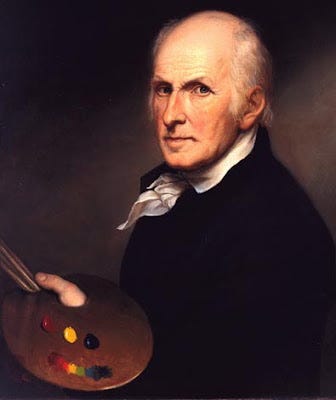

Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827) doesn’t show his working palette: after all, where’s the white? Instead he wants to let us know that he understands Isaac Newton’s theory of primaries and color mixing.

In the Middle Ages, artists kept their paint in shallow containers like shells or saucers, and expressed a dislike of mixing paint.

The first reference to a mixing palette was from an account of the Duke of Burgundy in the 1460s, where he described “trenchers of wood for painters to put oil colors on and to hold them in the hand.” Often palettes were set up by assistants, which helped standardize the procedure for laying out the colors.

The practice of mixing colors on a palette was common in the early 1500s. By 1630 it was a lively topic. Vasari said of Lorenzo di Credi that he “made on his palette a great number of color mixtures.” Above, Diego Velasquez painted himself in Las Meninas in 1656. Note the sequence: red and white, yellow, with dark and cool colors away from the thumb.

This detail of a portrait of Asher Durand by Daniel Huntington, reveals a typical arrangement, with light colors at the top, that is, near the thumb hole.

As this self-portrait by Milly Childers shows, often bright red pigments like vermillion were placed ahead of white because red was seen as a valuable, intense color, different from all the others and in a sense brighter than white.

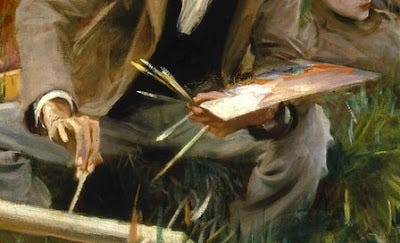

Above and below are by John S. Sargent. Blues, greens, and black went away from the thumbhole. The paints were usually placed on the outer edge, away from the body, which makes Paul Helleu’s layout (below) a bit puzzling—there’s a real danger of getting paint on his jacket.

References to palette knives show up around 1650. Elaborate premixed tints became a common practice by the late 1600s. During the next century artists more frequencly used a “loaded palette” with fully developed gradations of tints and variations. A Swiss painter’s manual in the 1820s compared the gradations on the palette to the notes of a piano keyboard.

Whistler was said to spend an hour preparing his mixtures. Delacroix’s assistant reported that it sometimes took days to set up his master’s palette.

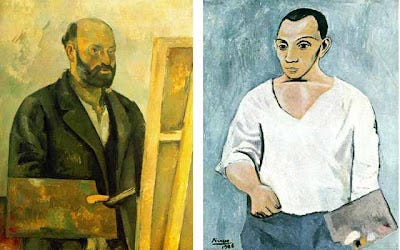

Cezanne (left) and Picasso (right) were evidently either ignorant or indifferent to these traditions, and showed their own palettes hanging vertically with a few confused and random smudges of color.

Now with the resurgence of realism and a revived interest in the craft of painting, palette arrangements are a hot topic again. Many artists work on a tabletop or taboret-mounted palette instead of a hand-held palette. Let me know how you set up your palette, and I’ll try to do another post in the future about contemporary methods.———

My main source for this post is Color and Culture: Practice and Meaning from Antiquity to Abstraction, by John Gage, Little, Brown, 1993.

I enjoyed seeing JMW Turner's palette when I visited Tate Britain in London a few months ago. Very cool!

I adore your pieces of art information which help todays artist either justify or alter their own thinking on add things art. You are a wealth of knowledge which you generously share. Thank you