"Blessing of the Young Couple Before Marriage" by Pascal Dagnan Bouveret

Houding

"Houding" is a term from the art theory of the Dutch Golden Age which has no equivalent in English. But like a lot of foreign art terms, its meaning can reveals insights into the thought process of artists from previous traditions.

Houding has to do with the "pleasing and effective evocation of space." Another translation renders it as "the tonal and spatial organization of the picture as a whole."

It combines several factors, including color, chiaroscuro, and atmospheric perspective, all working together to achieve a sense of depth and illusion. If the houding is successful, the colors are chosen and modified with depth and atmosphere in mind, placing "the powerful at the front, and the less forceful further back according to their nature."

Andrej Schilder, Russian, 1861-1919, The Ravine

According to a definition by Goeree from the time of Vermeer, houding is

"... that which binds everything together in a drawing or a painting, which makes things move to the front or the back, from the foreground to the middle ground and hence to the background to stand in its proper place without appearing farther away or closer, and without seeming lighter or darker than its distance warrants; so that everything stands out, without confusion, from things that adjoin and surround it, and has an unambiguous position through the proper use of size and color, and light and shadow, and so that the eye can naturally perceive the intervening space, that distance between bodies which is left open and empty, both near and far, as though one might go there on foot, and everything stands in its proper space therein."

Concepts such as houding remind us that the language that we're accustomed to using in twentieth century color theory is inadequate for painters interested in realism because it defines the universe in 2D abstract terms, detached from concerns of depth, light, and atmosphere.

Breadth

The term "breadth" was very important to 19th century painters, though it's rarely used today.

An 1847 manual of oil painting explains: “When the lights of a painting are so arranged that they seem to be in masses, and the darks are massed to support them, we have what is called breadth of effect, which is mainly produced by the coloring and chiaroscuro."

Breadth is related to the word "effet" in French, and "massing" or "shapewelding" in English.

The painting by Pascal Dagnan Bouveret is a good example of breadth. The white of the bride's dress joins with the tablecloth, the shaft of light, and the other women's dresses to make a single large shape. Meanwhile, two groupings of dark-clad figures join to form larger masses.

The painting manual says that breadth applies to both design and coloring, and that it is indicative of a master. Indeed it's difficult to achieve, because one must overcome the natural inclination to separate and define shapes throughout the composition.

Tenebrism and Chiaroscuro

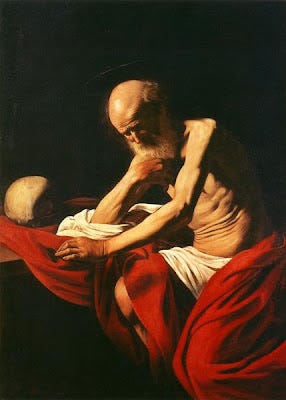

“Tenebrism” describes the use of bold contrasts between illuminated areas and shaded passages within a composition.

The effect conveys not only realism of appearance, but psychological tension. The term derives from the Italian word tenebroso, meaning "dark, gloomy, or mysterious," and is often associated with 17th Century followers of Caravaggio in Spain and Italy.

The closely related word “chiaroscuro” translates as “light-dark” in Italian. Generally it means the management of light and dark tones in a picture.

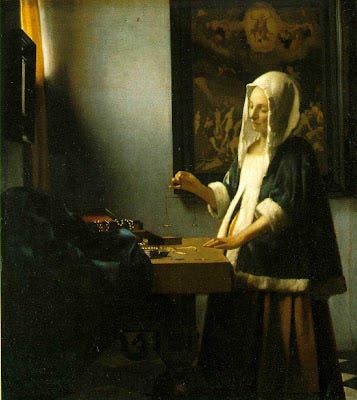

Note the separation of light and dark tones. Caravaggio doesn’t muddle around very much with transitional halftones or reflected light. To achieve this tonal separation with a posed figure, the model stand needs to be surrounded with dark cloth to suppress fill light.

Tenebrism and chiaroscuro are also often associated with candlelit scenes. In this painting by Georges De La Tour, the light source comes from within the picture and the overall effect is dark and dramatic. Note the subsurface scattering in the child’s fingers.

There’s another meaning of chiaroscuro having to do with form modeling in light and shadow. Peter Paul Rubens’ “Elevation of the Cross” is an example of this sense of chiaroscuro. The image has a bulging, rippling, “formy” appearance.

------

Goeree quote from the website Essential Vermeer

Other quotes from the paper "The Concept of Houding in Dutch Art Theory," by Paul Taylor.

Wonderful information! I love learning terms from you that I never came across in art history classes. 👏

That word, "houding" is wonderful. As I was reading it, I imagined how it could apply to one's life, overall: "pleasing and effective evocation of space."