The art of caricature may seem like something you either have a knack for, or you don't. But if you have a desire to learn, you can get good at it.

Fortunately there’s a book that lays out the expert knowledge behind the art, Tom Richmond’s The Mad Art of Caricature!: A Serious Guide to Drawing Funny Faces.

Richmond is best known as one of the "Usual Gang of Idiots" at Mad Magazine, but he has worked as a freelance illustrator for lots of other major clients. He got his start doing theme park caricatures in 1985.

David Lynch by Tom Richmond

Richmond explains how to analyze an individual's appearance to recognize what's unique about their head shape and their attitude. He talks about how to exaggerate the distinctive traits, rather than randomly distorting.

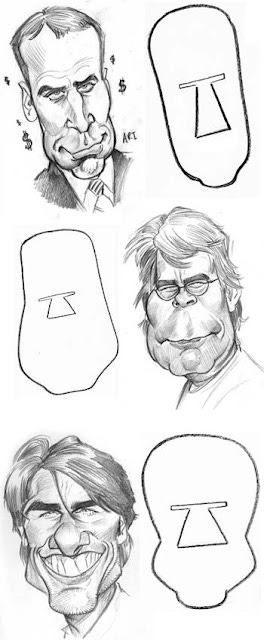

First you key in on the head shape, and then the main shapes within the face (eyes, nose, and mouth), and, importantly, the spacing between them.

T-Shape Theory

He analyzes each of the features, as well as the chin, cheekbones, and hair, considering carefully how they change with different angles and different expressions.

Instead of seeing the features separately, you learn to group them. Richmond came up with the "T-Shape Theory," where you group the eyes and nose into a single shape within the face, taking note of the length and width of the T.

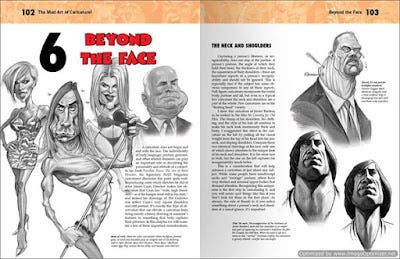

Tom is a good writer and teacher as well as a good artist, so this book is really worth reading carefully. The layouts are loaded with many drawings and diagrams on every page. It wraps up with a discussion of the challenges doing live caricatures, caricatures in illustration, and how he constructs a complex multi-figure scene for MAD magazine.

Which features should you make bigger?

Don't worry about which features to make bigger. Instead think about which ones to make smaller.

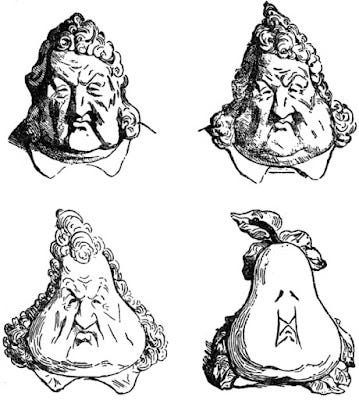

Louis Philippe as a pear by Honoré Daumier after Charles Philipon, 1831

If one part of the face must be big, make it bigger. Simplify, minimize, or reduce everything else. What you're left with after all this reduction are the essential shapes, the simple forms of the head and the hair. The most important thing about the features is their relative placement.

Caricature is not the art of accentuation. It's the art of reduction—reduction to essentials.

Even “realistic” portrait artists use caricature

When John Singer Sargent painted a portrait, he exaggerated the proportions and features to make his subject look more elegant and distinctive.

At left is a detail of Sargent's 1902 portrait of Lord Ribblesdale (Thomas Lister, 4th Baron Ribblesdale) alongside some photos of the subject in similar poses.

Sargent made many subtle accentuations. The head is smaller relative to the figure, making the figure look taller and more regal. Within the face, he made the outer folds over the eyes turn downward more dramatically.

Some of the differences in the folds and lines of the face may be explained by the aging of the subject, but Sargent changed the bone structure and proportions, too. He narrowed the jaw and lengthened the nose. These are all deviations away from the normal, standard face.

To be clear, the painting was done from life, not from photos, but the photo at center, taken in 1884, may have provided a starting point for Sargent's interpretation.

A contemporary cartoonist in Punch emphasized the absurd aspects of Sargent's interpretation. The note says "Regrets...Or Why did I Speculate on Such a Neck Tie? —J.S. Sargent."

One more example: Coventry Patmore by Sargent

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Paint Here to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.