Gammell on Art Teaching

Can an art school teach both mechanics and vision?

R. Ives Gammell (1893-1981) carried the torch for academic painting in mid-20th century America. He published Twilight of Painting in 1946, an argument for the value of traditional painting skills that he found lacking in the art world* around him.

Gammell makes an interesting point about art teaching:

“A painter’s training does not consist primarily in instruction as to the handling of his materials. Such knowledge is extremely important, of course, but it is not the main thing. The essential purpose of a painter’s training should be to equip him with the means of solving any problem suggested to him by his creative impulse.”

He argues that all painters must begin their inspiration with the visible world, and that “a sound tradition of painting is, perhaps more than anything else, an attitude toward the visible world, and its teaching seeks to make that world more understandable and more accessible to its disciples.”

He describes bad teaching as that which makes the student follow canned formulas for painting, or as he says, “ready-made interpretations of natural appearances and recipes for rendering them.”

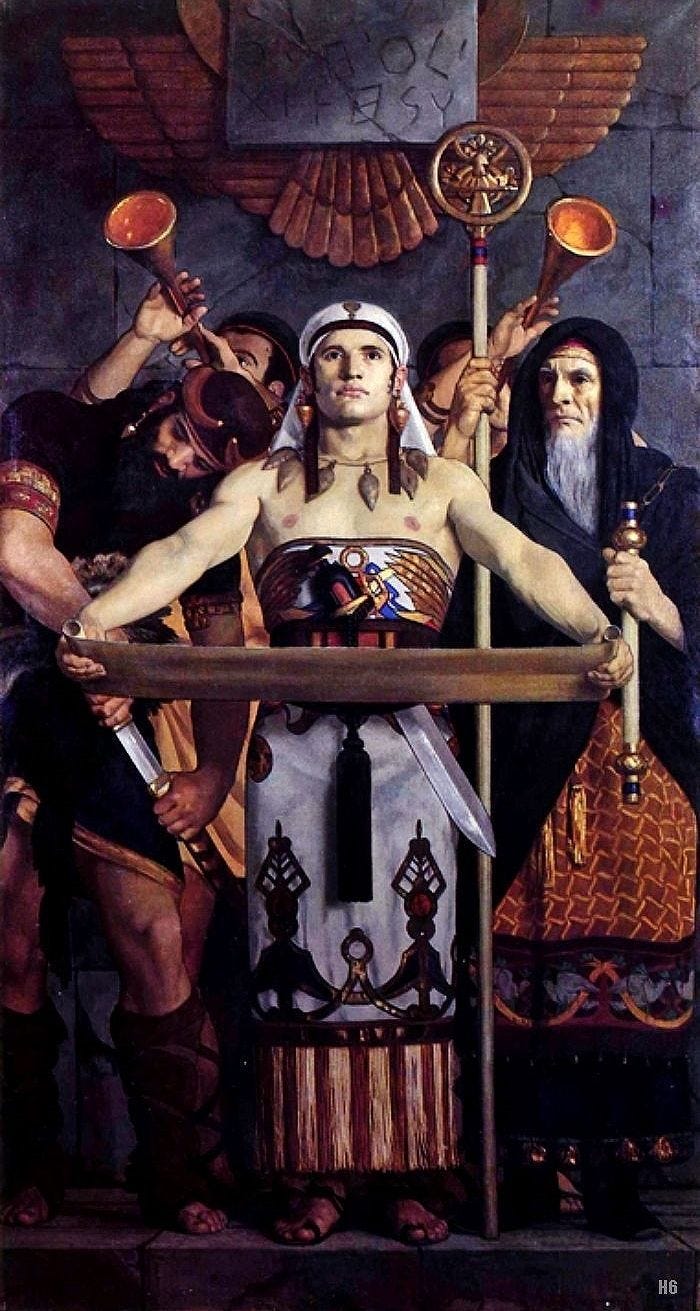

Above: Gammell: “The Law,” 1936.

How would Gammell address those higher goals? How, exactly, does the teacher equip the young painter to respond to the creative impulse? What good would such guidance be if the student didn’t already know how to stretch a canvas, and apply paint? Especially in a world where basic practical knowledge had been mostly lost, isn’t it the duty of an art education to have mastery of the mechanics of paint and brushes, perspective, anatomy, and accurate drawing?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Paint Here to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.