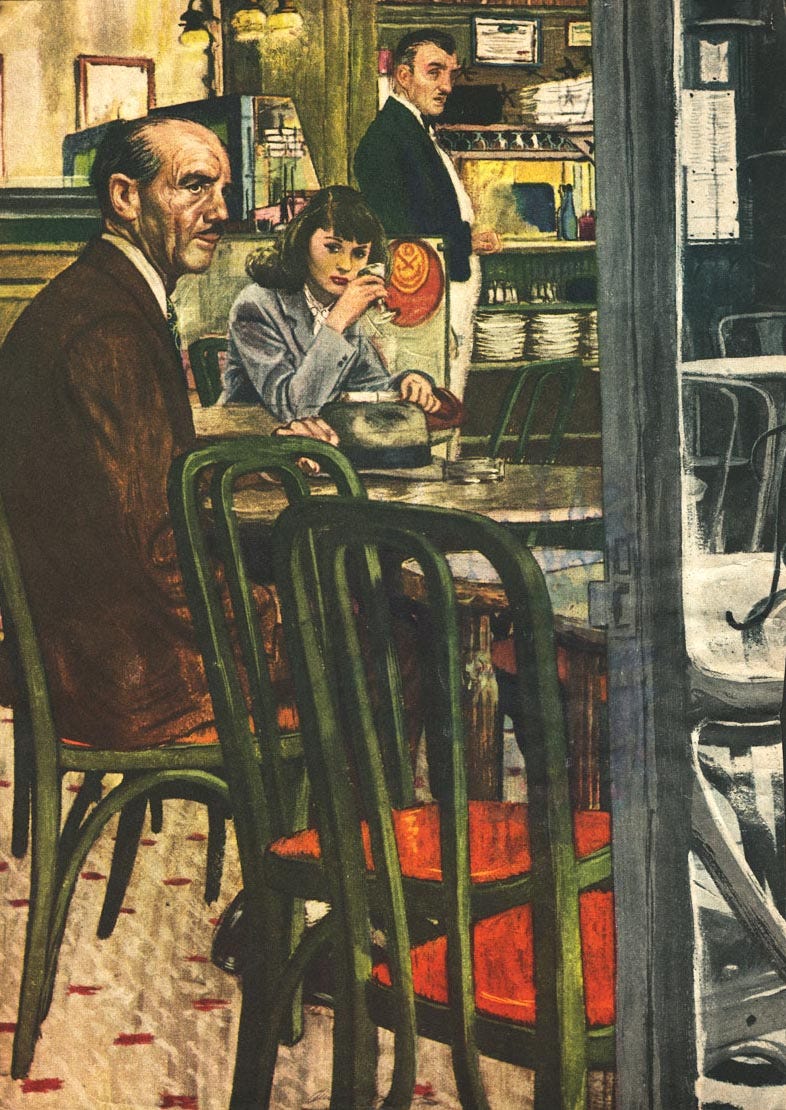

Austin Briggs (1908-1973) was born in a railroad car and raised on a farm with no books and no art. His mother never really understood him and his father and his sister died when he was young.

But he went on to become a leading illustrator in mid-20th century America. He wrote a master course for the Famous Artist’s School, and in that hard-to-find volume are some of the most eloquent thoughts about the art of illustration. He touches on the importance of originality, transcending restrictions, expressing emotion, and how to be a sponge. Since his writings don’t seem to exist on the internet, I thought I would share his introduction in full:

The Illustrator and his Art by Austin Briggs

“The first truth which any artist who wants to be an illustrator must face is that illustration is a job. The illustrator is a day laborer among the artists. He works hard, like a one-man ditch-digger, and he works alone.

“His paintings are made to order. They must comply with certain definite, predetermined restrictions, and they must be delivered to meet deadlines. Often the illustrator must accept assignments which do not particularly appeal to him, and make pictures which do not reflect his personal taste and inclinations. In spite of these facts, he must maintain definite standards of quality. He cannot afford to wait for inspiration to supply him with the answers, but unless his work is fresh, original, and imaginative he will find himself without future assignments. In a very practical sense he is only as good as his last illustration, so he must work constantly to maintain a dependable level of performance.

“For the successful illustrator, there is no eight-hour day. He must often work around the clock, conscious always of the fact that there are many others depending on him. The magazines and advertisers for which he works must be able to meet scheduled deadlines, or both they and he will be dead ducks. The illustrator's "workday" ends only when his picture is delivered and approved. His life cannot be organized on a nine-to-five schedule, nor can he count on a regular salary with time-and-a-half for overtime; but if he can meet the demands of his clients, his rewards, financial and otherwise, are considerable.

“Obviously, the illustrator is a commercial artist. But this is not all he is—nor can his work be limited to the lowest requirements of his craft. The fact that he works within rigid technical restrictions and other limitations does not necessarily mean that he cannot create noteworthy pictures. After all, the great masters of the past were subject to restrictions in many ways as rigid as those the modern commercial artist has to face. If the modern illustrator is a good artist, he will make good pictures. If he is not a good artist, he would not be able to make good pictures no matter how great his freedom.”

Next up: his thoughts on craftsmanship and expression, plus a poll and some bonus audio content:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Paint Here to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.